I’ve been 17 years as

a professional rugby

player, when you’re in the

job that long and then for

it to change all of a sudden

that can definitely be a

challenge.’ RICO GEAR

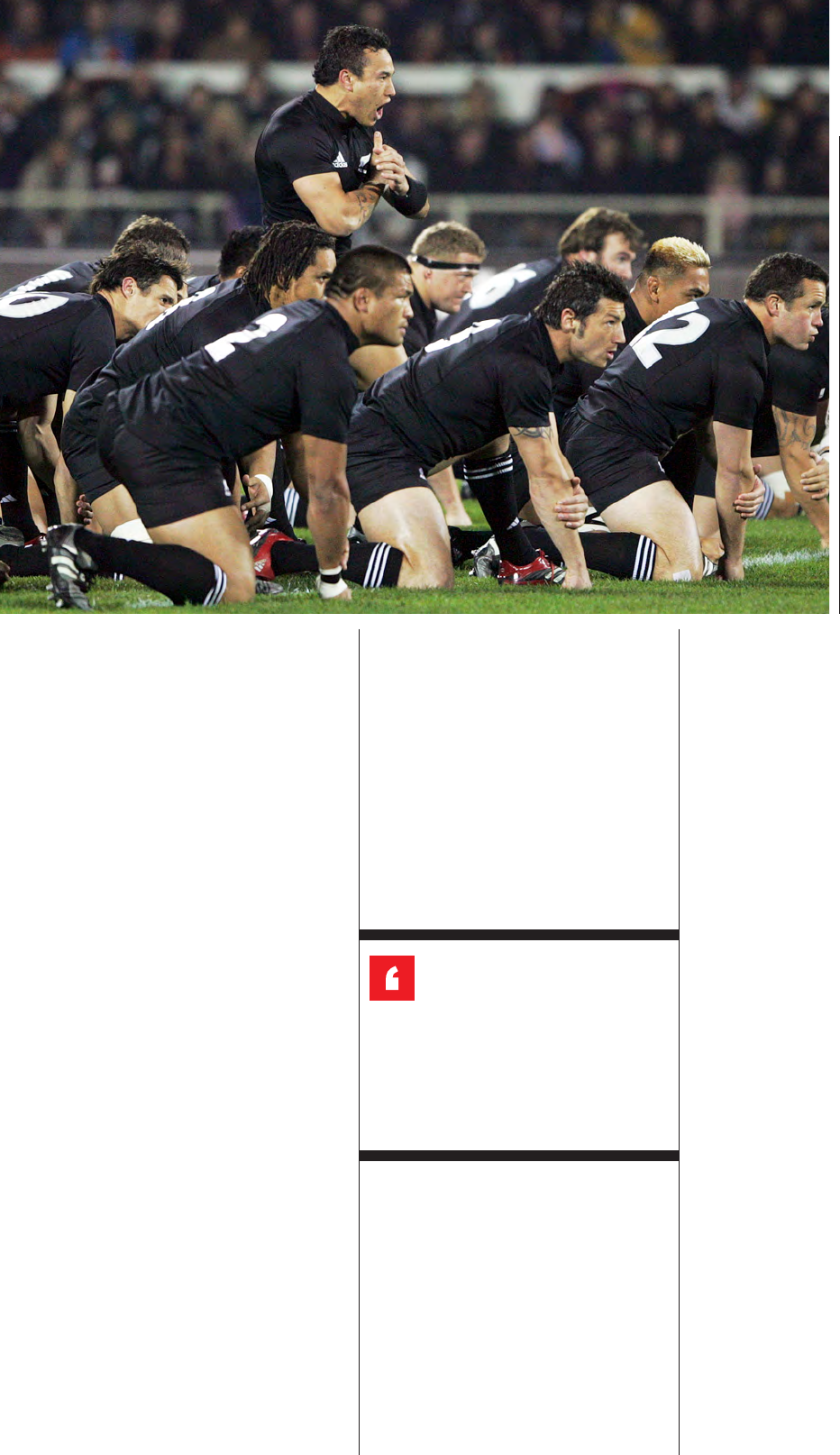

Umaga, Jerry Collins and Richie McCaw

following him. “Because I’ve been brought

up around the kapa haka scene, a lot of my

very good friends are, if you like, the elite

of the kapa haka circle. They’re the ones

who say to me, ‘Oh man, you’ve reached

the pinnacle of kapa haka. You get to lead

the All Blacks’.”

Gisborne Maori leader Derek Lardelli,

composer of Kapa o Pango, has been a

mentor and inspiration to Gear. “Derek’s

an amazing guy, with the amount of

knowledge he has.”

Lardelli created the striking tattoos on

the Gear brothers’ arms. “Hosea and I got

the tatts for each other in the early 2000s,

that’s what it really represents – our

family, us as brothers and how close we

are as brothers. And, of course, tie us and

keep us grounded with where we come

from. I’m still really stoked that I have it.”

Kapa o Pango faced poorly informed

criticism, particularly the motion at the

end of the haka. Gear is philosophical.

“That’s the tough thing I guess, when

you’re on the world stage the

understanding isn’t going to be there in

terms of what we know and what we

represent. It was definitely a tricky

situation in terms of the drawing of breath

and how we show that.

“At the end of the day, everybody came

together and made an agreement together

that we don’t go across the throat, we

draw from the lungs and go up from that

motion. That seemed to settle things down

a bit.” Like Hosea, Rico says leading the

haka is singularly intense. “You need to

know how to come back down. Sometimes,

because you’re so pumped up, you can be

on a different planet...as long as you’re

focused, you can show that ihi and wehi

through your eyes, and through your

actions, without going crazy. And again,

that controlled aggression which relates

to rugby where you need to be mentally

in control.”

In this vein, Gear has a last little pick me

up to get the Poverty Bay boys psyched up

before they hit the turf. “We’ve got a bit of

a Turanganui-a-Kiwa [Gisborne area] call

that we blast out before we run out of the

changing rooms. That’s been enough to get

everyone up, get everyone together and

away we go.”

He and Mutu created a mindset change

within Poverty Bay, Gear says. “We gave

the boys more knowledge in terms of what

we represent when we talk about the

players and the legends of this area who

have won the jersey before, to give it more

mana. We try and create more culture that

way. The challenge was to bring them

together as well because we have got a mix

of players in Gizzy here. We’ve got quite a

strong Maori population and we’ve also

got our Pakeha brothers, all our farmers,

and we’ve got a couple of Tongans as well.

Trying to bring them together and get

them all on the same waka.”

Just as the Chiefs have employed Tainui

culture to success, Poverty Bay learn from

the wisdom of local tribes such as Ngati

Porou, Mahaaki and Rongowhakaata. “We

also use other legends that are here, the

likes of Ian Kirkpatrick, he’s a local

resident. We draw on those guys, get them

into the environment and try to have them

around as much as possible. It gives the

boys a lift, when they’re rubbing shoulders

with them and talking with them about

their experiences.”

Kirky and Lawrie Knight played many

games for the Bay in the days when they

played against the top provincial teams in

New Zealand. “My brother [Hosea] played

for the Hurricanes for a long time and he

spoke of Kirky being in there, just how

good it was to have someone like that, of

that stature, in the environment. And it’s

been great for us as well.”

Gear and his players really enjoyed

hosting the Hurricanes’ first 2015 camp in

Gisborne. “We definitely maximised the

time we had with them. You could see

from how they were gelling as a unit that

they were going to potentially do really

well, leading into the tournament.”

He’s energised about the Heartland

Championship ahead. “This year’s the

125th anniversary year for the Poverty Bay

union, so it’s a celebration year.”

Another reason for him to come home

was for his young children to go to good

local schools, and have access to Maori

language and culture. “So that’s the great

thing for them to be exposed to and the

tikanga on the marae.”

Players can find the transition out of

playing professionally full-time quite

daunting. “I’ve been 17 years as a

professional rugby player, when you’re in

the job that long and then for it to change

all of a sudden that can definitely be a

challenge. At the same time I am grateful

that I’ve now come into a role which is still

heavily involved in rugby. I think that’s

made the transition easier. My partner and

I also run a nutritional cleanse business,

which is certainly keeping us busy.”

The coach/occasional player combo

invites comparison with former teammate

Tana Umaga. As much as Gear is

appreciating starting his coaching career

FULL BLOODED

Growing up in Poverty

Bay, Gear has developed

a deep connection with

the haka and his Maori

roots.

64

// NZ RUGBY WORLD / JUNE/JULY 2015

[ RICO GEAR ]